The fortified cities on the fringes of the Sahara

Africa's largest nation

Stretching between Morocco and Tunisia and facing Europe across the Mediterranean, Algeria is Africa's largest nation and the 10th largest in the world. Its vast and varied landscape of soaring mountain ranges, blistering deserts and ancient Roman ruins covers nearly 2.4 million sq km – 10 times the size of the UK.

Much of the country – around four-fifths – is consumed by the Sahara, the largest hot desert in the world and a startling, barren wilderness of volcanic massifs, gravel plains and great ergs, or shifting "sand seas". One of the largest of these is the Grand Erg Occidental (pictured), whose seemingly endless expanse of windswept sand dunes covers an area twice the size of Belgium. (Credit: Simon Urwin)

Centuries-old settlements

While few Algerians live in such hostile terrain, a chain of extraordinary hilltop settlements exist on the northern fringes of the Sahara: the five historic ksours, or fortified cities, of the M'Zab Valley. Collectively known as the Pentapolis, these magnificent, centuries-old citadels were built along the Wadi Mzab, a partially dry riverbed whose waters rise just once every three to five years. The towns include El-Atteuf, the oldest, founded in 1012; Melika; Bounoura; the Holy City of Beni-Isguen; and Ghardaïa (pictured), the principal settlement and commercial heart of the valley. In 1982, the M'Zab was classified as a Unesco World Heritage site due to its highly distinctive culture and architecture.

"What makes the place so special is the unique combination of [the indigenous people of North Africa] with Ibadi Islamic beliefs who built fortress homes in the middle of the desert," said local guide Khaled Meghnine. "There's nowhere like it in Algeria, nor the rest of the world." (Credit: Simon Urwin)

Ancient origins

Home to a modern-day population of more than 360,000, the cities of the M'Zab were established by the Mozabites, a semi-nomadic people with their own distinct language, Tumzabt. The Mozabites had already been exploring this part of Algeria since around the 8th Century, but faced with the region's growing desertification, they chose to settle and adapt to the harsh environment. They built their cities between the 11th and 14th Centuries, each centred around a mosque with a turreted minaret-cum-watchtower. On the valley floor, the Mozabites established palm groves that also served as an escape from the summer heat.

"It's incredible how their society managed to flourish in such inhospitable climes," said Meghnine. "It's why the people treasure their culture. It has survived against the odds for over 1,000 years, so they do all they can to keep it alive and strong." (Credit: Simon Urwin)

A compact labyrinth

In each city, the Mozabites constructed a compact network of streets: the narrowest were only wide enough to accommodate a donkey carrying goods, while the main thoroughfares to and from the market were built to fit a camel. Their box-shaped stone houses had room inside for a goat that provided milk and consumed leftovers. "Apart from electricity coming in the late 1950s, daily life in the historic centres has changed little since the cities were founded, and that's how the people like it," said Meghnine. "Queuing etiquette at the water pumps remains the same: children first, then women and men. The practice of painting outdoor walls blue to keep the space cool and deter mosquitoes continues to this day."

Another convention sees women spending much of their time at home within the high-walled courtyards that provide requisite privacy. "In Beni-Iguen, these are visible from the watchtower, so outsiders are barred from entering the city and climbing the tower until after the afternoon prayer. It ensures women can still spend the day outdoors unseen,” said Meghnine. (Credit: Simon Urwin)

Strength from unity

Many centuries ago, the Mozabites converted to the conservative Ibadi school of Islam from the Mu'tazila school of Islam, and the M'Zab Valley is now one of just three significant Ibadi communities in North Africa – along with Djerba in Tunisia and Jebel Nafusa in Libya. "Ibadis are known for their community solidarity and tolerance," explained local guide Elghali Laggoun. "Historically, they've always co-existed and co-operated well with others. In times past, they'd give their goatherds over to the care of an Arab outside the city walls; the Mozabites weren't natural shepherds, but the Arabs were. Similarly, they'd go to the Jewish population to buy their copperwork and jewellery. There is still a Jewish community here, also a Christian church. To survive in the desert, you need the strength that comes from unity – that's something that everyone in the M'Zab strongly believes in."

One of valley's most famous Ibadis was the religious leader Sheikh Sidi Aïssa, whose striking tomb (pictured) is in the cemetery of Melika. (Credit: Simon Urwin)

Tradition over commerce

Religious councils have long held sway over the M'Zab. Each assembly contains key community figures including the imam (or worship leader), the muezzin (who calls Muslims to prayer) and a teacher from the madrasa (Koranic school). In Beni-Isguen, the most conservative of the cities, the council's judgment is called upon for a wide variety of spiritual and moral matters.

"Recently, some merchants wanted to turn some of the buildings of the central square (pictured) into shops," said Meghnine. "The council forbade it because they saw the square as a place of social cohesion. Anywhere else in the world this would be full of gift shops, but here it remains a quiet place to come and sit with your family and to get to know your neighbours. Meeting up in the square is considered a necessity. There's even a local saying: ‘Any man who doesn't go must be sick or have a bad debt.' So the religious council made their decision to help keep the community strong. That's more important than money." (Credit: Simon Urwin)

No hawking, haggling or modern signs

In the larger city of Ghardaïa (pictured), trading is allowed in and around the central market square, but modern signage and advertising are banned so that the city retains its original 11th-Century appearance. By local decree, side streets can specialise in just one product – be it carpets, fruit and vegetables or gold. "A Mozabite merchant doesn't think of the other shops as rivals," explained Laggoun. "Instead, he relishes the company of other vendors, knowing that their being together helps cement the strong community ties."

The hawking of wares and haggling over price are both frowned upon here and elsewhere in the M'Zab. "It stems from the Ibadis' strong belief in equality: the seller respects the buyer as an equal so they are honest with them and offer a fair price from the start. The importance of equality here goes beyond trade too. At a social event, you could have the richest and poorest people of the valley in attendance. But they'd eat and drink together as one, because all people are seen as equals," Laggoun said. (Credit: Simon Urwin)

Conservative dress

While some of the younger generation in the M'Zab are slowly adopting a Western style of dress, many residents still opt for more traditional attire. Conservative women wear a white woollen shroud, known as a haik, when they step outside the home; while boys and men sport tchachit, or skullcaps, and saroual loubia – pleated baggy trousers, much like harem pants. "The saroual are practical because they keep the wearer cool, and also allow for flexible movement during any kind of physical work," a local English teacher told me. "I also like them because they are part of the uniqueness of M'Zab identity. After all, if everyone wore jeans and a football shirt, we'd look just like the rest of the world." (Credit: Simon Urwin)

Water is more precious than gold

There are more than 100,000 palm trees in the valley, and the palm groves, much like the cities, are subject to their own exacting rules. A dedicated water council monitors usage of the supply that comes from aquifers deep beneath the Sahara, and there are punishments for those that take more than their fair share. "Not a single drop of rain fell in the M'Zab between 2008 and 2017 so it's no wonder that water is considered more precious than gold," said one palm grove farmer. "It's why the regulations are taken so seriously and why rule-breakers may be cast out of society for committing a grave wrongdoing." Another rule prohibits any of the living date palms, or "holy trees" as they are also known locally, from being felled.

"Killing a palm in the M'Zab is as unthinkable as killing another human being," he said. "It would be an unpardonable sin." (Credit: Simon Urwin)

Coffee from dates

Every year the M'Zab's palm farmers follow an age-old pattern of cultivation and harvest. Their trees are fertilised by hand in April when the male inflorescence is tied to a cluster of female flowers and a prayer is said to ensure a bountiful yield. The date fruits begin appearing in May and June, with the first crop reserved for Ramadan. "It was said that the Prophet would break his fast during Ramadan by eating ripe dates just before praying," said the farmer. "So, eating them the same way still has great spiritual significance for us."

Discarded pits are traditionally used as animal feed or roasted and ground to make a kind of Mozabite decaffeinated coffee. "Even though we can buy coffee in the grocery store, we are desert people at heart. We always find a way to make sure that anything God-given doesn't go to waste," the farmer said. (Credit: Simon Urwin)

Sustainable tourism with a conscience

In Beni-Isguen, where there are no hotels, restaurants or coffee shops, simple tourist facilities have sprung up in its nearby palm grove. "The M'Zab is not a resort. It's a real place, full of real people," said Salah Daoud, the manager of a homestay (pictured). "Staying with a family offers an authentic, immersive experience of the valley. The food is homemade: a local lady makes our couscous and we buy camel meat from the [local] butcher, so the experience also includes the wider community."

There are now some 30 such homestays across the M'Zab, with tight limits on tourist numbers. "There's a clear understanding here of the difference between mass tourism and sustainable tourism with a conscience," said Daoud. "We are focused on the latter. The last thing we want is to be overwhelmed with tour buses and the M'Zab turned into a human zoo." (Credit: Simon Urwin)

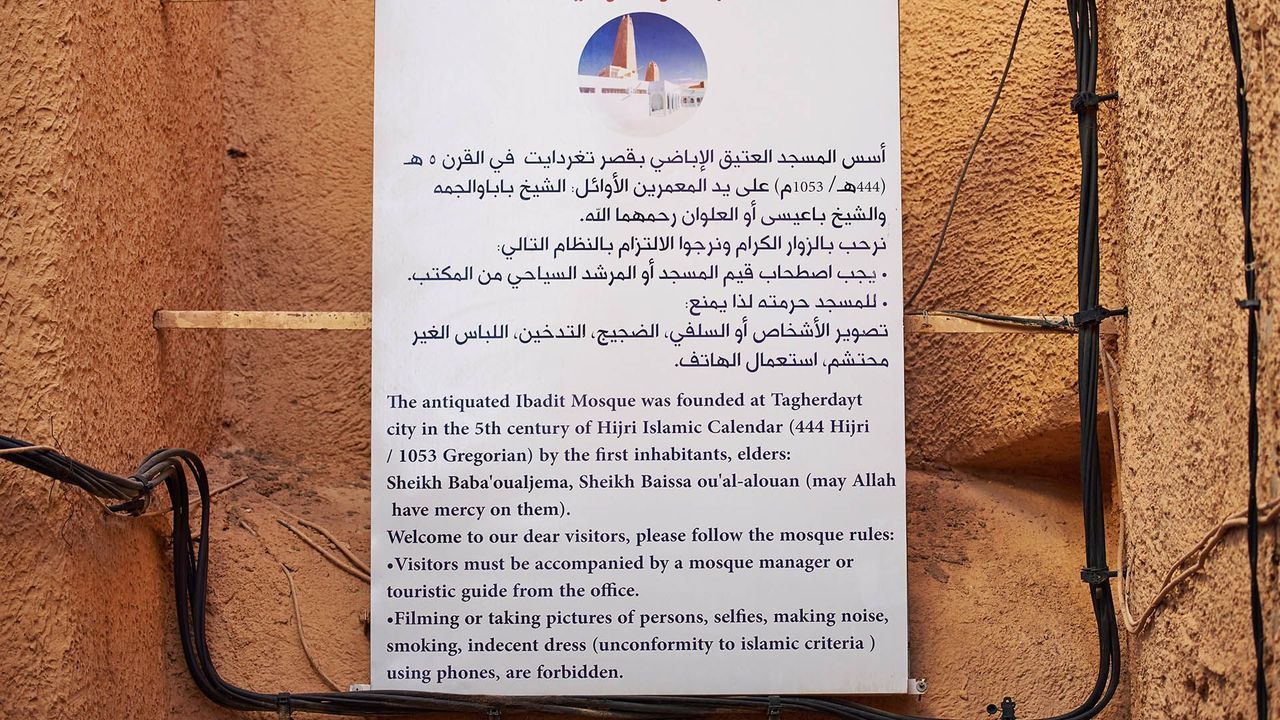

No selfies allowed

One regulation, encouraged by the valley's tourism board, dictates that all visitors, including Algerians, can only enter the five fortified cities accompanied by a local guide. "We see it not as a job, but a duty," said Meghnine. "We do it to protect the cities because we cherish the way of life."

Tobacco has long been prohibited in the historical centres for religious reasons, and numerous signs indicate other banned behaviour, including the taking of selfies, the wearing of indecent dress and the use of mobile phones. "We are very friendly people, and visitors are most welcome, but we kindly ask that they respect the Mozabite way of life," said Meghnine. "It is our home after all, not just a backdrop to an Instagram post. We don't want the M'Zab turned into a kind of Saharan Disneyland." (Credit: Simon Urwin)

Note: All photography in this story adhered to local guidelines.